KUALA LUMPUR, Aug 14: Deforestation and the sale of forest land to “timber-hungry” investors has been steadily continuing over the years in the state of Kelantan, which remains one of the most badly affected states during the year-end flood season.

While every year, the support of federal government as well as corporate bodies and NGOs, running into millions of ringgit, go to Kelantan during its rainy season, the state government has not made much progress in its flood mitigation measures, nor has it reduced its deforestation, which has been long proved to be a barrier against heavy rain and floods.

Whether an increase in funding from the federal government to Kelantan and other states to protect their forests and reduce carbon emissions, have done much or have been used for conserving the forest grounds cannot be established.

According to a source, investors from outside Kelantan, where only Kelantanese can buy land, have been “using cables in the state” to buy forest land so that they can go into the lucrative timber business or plantation business.

Most of these lands are acquired under the agriculture license, with the help of locals and they “are told to quickly clear the land of its woods,” and carry on with “sustainable agriculture crops.”

One businesswoman, whose family has aquired some “agriculture land” says they have been “struggling to clear the land and it has not been easy to do it fast as these are difficult jungle terrains”.

It cannot be established if the woman’s affiliation to a political party made it easier to acquire the land. It cannot be also established how many more investors or foreigners have acquired forest land in Kelantan to carry out the work of chopping of trees and turning the areas into agricultural land.

To a question on whether the land sale are made in exchange for political support, the source said even if this was the case, it cannot be proven.

A drive along the Grik road connecting Perak and Kelantan, one would be able to see with their own eyes, the huge timber logs all tied and piled up in huge lorries, being transported, possibly to a port for export or to another destination in the country.

It is a lucrative business, but several questions can be raised. Kelantan has been exploiting its huge forest reserves for decades. Should it not be one of the richest states in the country?

Why then is it claiming to be the poorest and continue to depend on federal funds to clear its floods? Where are the revenue from the timber and other forest related and land sale business, which is state managed, going to? Are the people of Kelantan benefitting from this source of state revenue? Has there been enough transparency in the way Kelantan spends its revenue from its quickly disappearing forests? How many foreign companies have been given the concessions to clear state forests?

How much of its income has been used for sustainability plans or experts to study the impact of its deforestation activities on its low lying areas over the years?

In 2014, the late Menteri Besar of Kelantan, Nik Abdul Aziz, expressed deep regret over some investment decisions following the devastating floods that year. But it remains unclear, exactly what investments he was talking about, although it was in referrence to the floods.

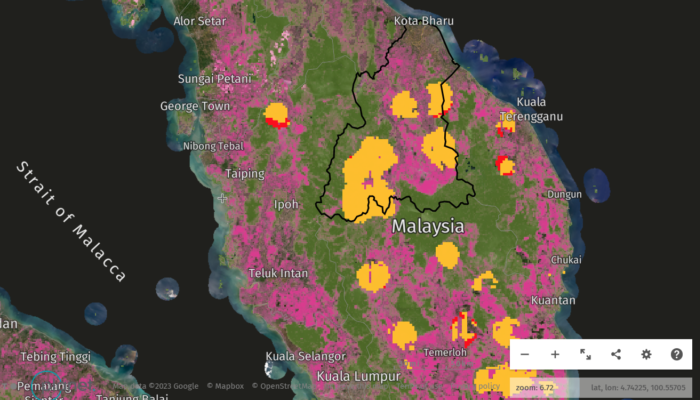

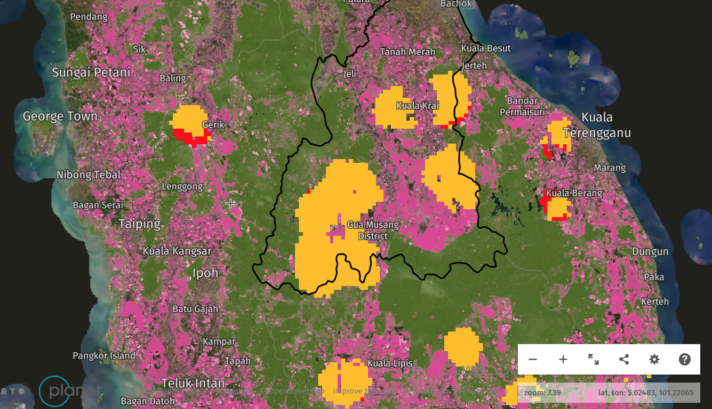

Statistics from Global Forest Watch (GFW) showed that there were about 1,200 fire alerts in the early week of August with 209 of these fires in primary forests areas. Fires have been indicated almost all states in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah and Sarawak. Deforestation alerts were not only seen in Kelantan but in almost all other states.

In Kelantan, a total of 1,488,755 deforestation alerts were reported between February 10, 2022 and August 13, 202, covering a total of 18.3 thousand hectares.

From 2001 to 2022, Kelantan lost 168kha of humid primary forest, making up 37% of tree cover loss in the same period. Total area of humid primary forest in Kelantan decreased by 23% in this time period.

In the last two decades, Kelantan also saw a loss in tree cover amounting to 452 thousand hectares, equivalent to a 34% decrease in tree cover since 2000, and 288Mt of CO₂e emissions.

Many of the investors, legal or not, in order to make a faster clearance of these forests, also choose the burn and slash method or just slash method. However, the regrowing of these forests cannot be as easily done and no matter what the claims of sustainability, the damage is quite irreversible.

While climate change is easily cited now for the rains and floods, the monsoons in Kelantan are regular, except that they may just get worse without the barrier of water soaking trees and mud rains will continue to get muddier. It will continue to get more costlier for the federal government to keep Kelantan “afloat” during floods, leave alone the state government.

With the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) all set to link the state with Port Klang, transportation of timber, might be made easier. Whether legally or illegally sourced, this would certainly need strict supervision of goods going into the train, the source said, but added that that will be another issue altogether and a problem still few years ahead.

Meanwhile, the state of rainforests in Kelantan, Pahang, Terengganu as well as well in Ulu Perak, and in Kedah, another notorious state known for its dalliances with foreign parties to explore, exploit its forests, will continue to remain under scrutiny.

During a recent exposure where Kedah’s state leader was reported to have been responsible for the illegal mining of rare earth, environmentalists took note that the focus was more on the illegality of the mining and very little attention was paid to the fact that the mining had taken place in a forest area, where deforestation would have been inevitable to conduct any mining activity. Would legally mining in the forest area with the revenues declared been more acceptable?

In Selangor, which is already almost fully developed and only few forest areas are intact, questions have been also raised on the environmental impact that some ongoing and future projects will have on the remaining green areas. Some questions have remained unanswered.

While Malaysia has been making slow progress towards its net-zero greenhouse gases emissions pledge including its transition to a greener economy with plans for the adoption of more renewable power sources or plans for more electric-vehicles amid a changing climate, its focus on one of the most important weapons to face climate change – its rainforests – has been almost nil.

The forests, at least the remaining ones, are still seen as firstly resources more than as solution to tackling green house emissions.

While a commendable move has been made by the Natural Resources, Environment and Climate Change Ministry to form a panel of advisors on all matters related to environment and climate change, there has been very little information on the compositioin of the body. There has been also no mention of any activist or NGOs sitting on the panel.

The search or innovation towards keeping its forest intact and moving into economies that might bring less revenue in the short term but more value in the long term could be ramped up.

— WE