by Trailerman Sam (tapessam@gmail.com)

When I mentioned Manicasothy Saravanamuttu, or Uncle Sara to many, in one of my articles months ago, I got a text message from a friend, Kenneth Spledewinde, a Malaysian of Dutch origin.

To melt it down further, he was a descendant of the Ceylonese Dutch Burghers as the Dutch had settled in present-day Sri Lanka centuries ago. Kenneth is the son of Harold Spledewinde, the personal bodyguard of Sara before venturing into the plantations sector himself in Malaya.

Kenneth’s message read: “Uncle Sara was a very close friend of the family. He came from Sri Lanka on the same ship as my grandparents. He lowered the Union Jack from the flagstaff at Fort Cornwallis when the British administrators evacuated in World War II.

“Then he organised an emergency committee from different communities to restore civil administration (in Penang). He was at the Church Street Pier to meet the Japanese (soldiers) when they came across the (North) channel in sampans. Uncle Sara asked them not to harm the (local) citizens. A real hero not forgotten by those who knew that part of local history.”

Now if that’s not a heroic action to safeguard the lives of the common citizens of Penang, what else could it be described as?

As the saying goes “Live today to fight another day, innocent lives come before pride and loyalty.” Not like some politicians today who have got the knack of harping on the trifling but toxic issues just to gain popularity.

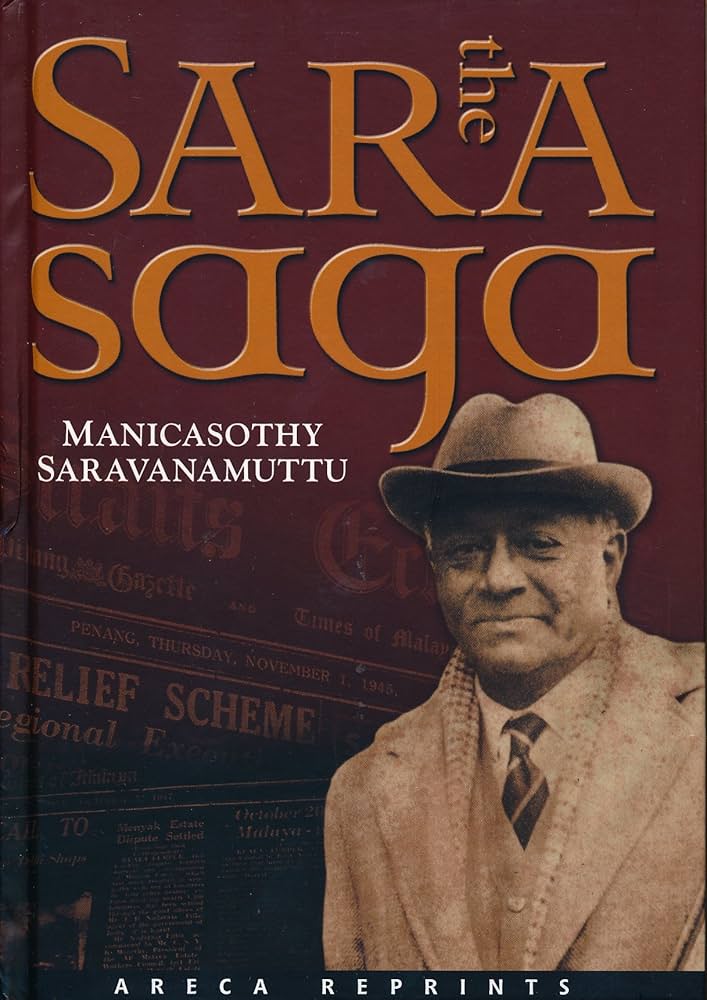

Sara’s heroism is contained “The Sara Saga, Manicasothy Saravanamuttu”, an autobiography first published in 1970. The one I have is a reprint published by Areca Books. I recently was out of books to read after my series of surgical procedures at the Alor Setar General Hospital. So, a book in hand will help to overcome my blues.

I chanced upon this book when I was browsing the Internet looking for a good read. A local online bookseller was offering it for only RM27.12. I grabbed the offer.

Back to the book: With 17 chapters in all, they’re neatly synchronised and don’t jump from one era into

another. There are also 57 illustrations in the reprint, all in black and white.

The book starts with acknowledgements and a foreword by none other than the then-British Commissioner-General for Southeast Asia, Malcolm McDonald, who had a unique approach to the decolonisation of British colonies in Asia. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, MacDonald suggested combining Sabah, Sarawak, Singapore, Brunei, and Malaya into a single region or entity known as “Malaya Raya.”

In Chapter 5, you will find an amazing narration of how Sara ran the Straits Echo newspaper against its strong rival, The Times of Malaya. For many years, The Straits Echo was the leading newspaper in northern Peninsula Malaysia or Malaya. It was even touted as the best newspaper East of Suez at one time!

Sara also wrote about bombs being dropped by Japanese warplanes on just outside the Straits Echo’s office along Penang Road, being thrown into prison by the Japanese and being branded as a traitor by the British for bringing down the Union Jack at Fort Cornwallis when the Brits abandoned Penang altogether.

These events only made Sara adapt and become more stronger in the face of adversity and trauma.

For the record, Sara became a student at Oxford University after World War I. In the book, he mentioned a famous St. John’s vs. Trinity cricket match he played in, in which the Trinity wicket was kept by Edward Gent, who later became Governor of the Malayan Union.

Unfortunately, Sara was unable to complete his undergraduate course at Oxford and left without taking a degree.

In his autobiography, he described of being caught by the university’s proctor while he was staggering down the high street with a friend in the summer of 1919, having celebrated “lavishly” after being elected a member of the “Authentics” (an Oxford University cricket team).

Both were sent back to their college or hostel after the incident. While Sara’s friend was merely sent down or “rusticated” for a term, the Ceylonese, being a Colonial Student, was reported to the Director of Colonial Students to whom it was recommended that he be “sent to a university nearer to home”.

Sara wrote that he received a letter signed by Sir Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, informing him that a passage had already been booked on a ship back to Malaya.

Sara chose not to undertake this journey out of “shame” at being sent home so ignominiously and remained in London for some time. Interestingly, he has been described as not having any rancour for the treatment he received for the very reason that “he was a Colonial instead of a Home Student” while writing his autobiography.

On his return from Oxford, Sara worked for a newspaper in Ceylon, and then became editor of the Straits Echo in Penang, thus becoming the first non-white Chief Editor of a Malayan newspaper, under whom many post-Independence Malaya’s leading journalists trained.

After the British pulled out from Penang in 1942, Sara was credited for having “raised the white flag” over Fort Cornwallis and led the organisation of food, fuel and essential services, for the local population. After the war, Sara served as a diplomat, representing Ceylon in Singapore, Malaya and Indonesia, and was also on the Organising Committee of the first Asian-African Conference at Bandung, Indonesia, which laid the foundations for the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

The Weekly-Echo, which takes its name after The Straits Echo, is proud to recount the heroics of Sara, whose autobiography is a must-read for students of Malaysian history.

–WE