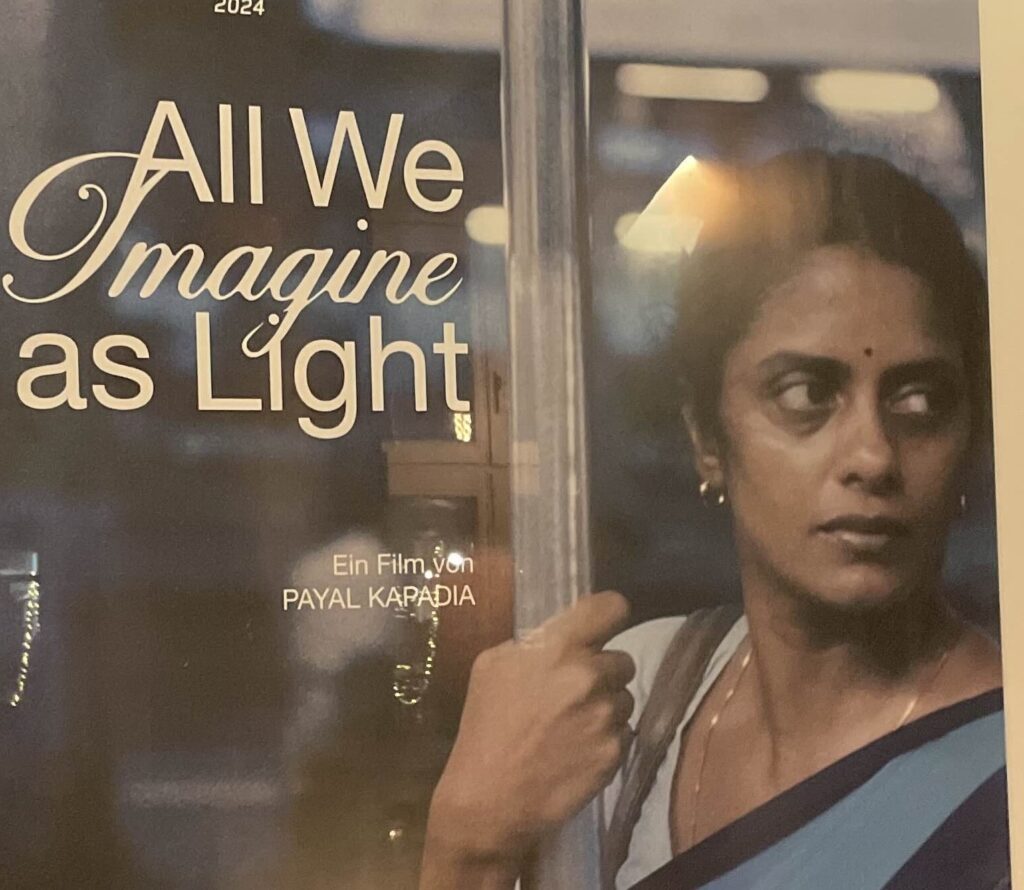

All We Imagine As Light – Unconventional, Profound and Uplifting

by Neshalatha Govarthnapany

The Indian cinema industry is often synonymous with fantasy-driven narratives, but All We Imagine as Light stands apart as a profound, unconventional tale. Though slow-paced, its simplicity unveils a deep exploration of the ongoing transformation of women in India, blending practicality with artistic nuance.

The story revolves around the bond forged between three ordinary Indian women of different ages, united in their struggles and dreams as migrants in bustling Mumbai. These women, each seeking a better future, navigate the complexities of life with resilience and grace.

The central character, Prabha (played by Kani Kusruti), is a married nurse trapped in the uncertainties of an arranged marriage. Her husband, who left for Germany shortly after their wedding, gradually ceases all communication. One day, Prabha receives a rice cooker made in Germany, presumed to be from him. In a poignant scene, she clutches the rice cooker tightly, a silent portrayal of her longing for his presence. Despite her loneliness, societal expectations compel her to remain stoic and faithful. A doctor at her hospital expresses romantic interest, and while she shares his feelings, she avoids acting on them, suppressing her emotions and desires.

Prabha’s roommate, Anu (played by Divya Prabha), offers a contrasting perspective. A young nurse, Anu defies traditional norms by pursuing a forbidden relationship with Shiaz, a Muslim man. Their clandestine meetings provoke gossip, yet Anu remains undeterred, embracing her freedom to explore her choices and sexuality. Her defiance of family pressure to accept an arranged marriage highlights her determination to chart her own path.

The third woman, Parvathy (played by Chhaya Kadam), works as a cook at the hospital. A widow facing eviction from her home by developers, she embodies resilience in the face of injustice. Prabha’s attempts to secure legal aid for her are futile due to missing documentation tied to Parvathy’s late husband. Ultimately, Parvathy decides to leave Mumbai and seek opportunities in her village. Despite her struggles, she radiates positivity, finding joy in small moments like dancing while sipping on whiskey or taking a dip at the beach in her saree. Her outlook underscores the power of embracing life’s beauty amidst adversity.

Director Payal Kapadia captures these stories with poetic grace, portraying Mumbai not as a city of dreams but as one of illusions. The film delves into the paradox of migration: the pursuit of a better life often comes with unequal struggles. The narrative also touches on gentrification, with the stark statement “Class is a privilege reserved for the privileged” displayed on the construction site where Parvathy’s home was taken away.

What resonated most with me was the theme of dissent. The women in this film challenge traditional definitions of marriage and life choices, courageously confronting their suppressed needs and desires. Prabha’s decision to seek closure and move on from her estranged husband stands as a powerful act of empowerment, defying societal norms and the patriarchal system.

Similarly, Parvathy’s story subverts expectations: rather than lamenting the absence of a male saviour, she takes charge of her circumstances and chooses to live independently, even though she could have sought support from her son. How can one truly understand their needs without the space to explore themselves, especially when their lives are often dictated by others? In Indian families, such decisions are typically made by a male figure—whether it’s a father, an elder brother assuming leadership in the father’s absence, a husband after marriage, or even a son in the absence of a husband. This cultural norm has perpetuated a cycle where many Indian women have historically sacrificed their desires for the needs of

their families.

In a simplistic yet poignant way, this movie reflects the ongoing transformation among women today—a movement toward independence, autonomy, and having a voice in their own lives, rather than sacrificing their desires for the sake of others. Another striking element is the film’s realistic portrayal of women. The characters wear ordinary clothes, bear dark circles under their eyes, and have unshaved legs, eschewing the polished perfection often demanded of women in mainstream cinema.

This unvarnished representation adds authenticity to their stories, but also acts as an example to other women, encouraging them to embrace themselves as they are and to decide how they want to present themselves to the world. With the typical Indian notion that beauty is defined by how fair one’s skin is, the

absence of body hair, and the use of thick makeup, this film challenges these entrenched ideals.

Watching this film in a Berlin cinema was particularly striking, especially in the context of feminism’s rise in Europe. It sparked a rich conversation with my Berlin-born friend, contrasting the struggles of women in contemporary India with those in Europe. It also prompted personal reflection on my journey as a brown woman. The sacrifices made by my mother and the women of her generation paved the way for the independence I and many other women now enjoy—freedoms that previous generations could not even dream of. My maternal grandmother who got married at 14, was expected to raise a family, while my paternal grandmother faced shame for remarrying as a young widow. Their stories stand in stark contrast to the choices available to me and other women of Indian descent today. It fills me with hope for future generations, including my nieces, who will grow up with the autonomy to define their own happiness and independence, free from the belief that life’s accomplishments are tied to marital status or the sacrifices they make for others.

For some, this may be just a movie, but as an Indian immigrant descendant, it feels deeply

personal.

Neshalatha Govarthnapany (Nesha Pany) is doing her Ph.D specialising in Addiction Science at Charles University, Czech Republic. Recently relocating to Italy as part of her doctoral journey, she embraces the chance to explore Europe while staying deeply connected to her roots in Malaysia. With over a decade of experience in Malaysia’s public healthcare system, she has dedicated her career to serving marginalised communities, including individuals living with HIV and those battling drug addiction. Alongside her research, Nesha practices alternative healing, embodying a holistic philosophy on life and well-being.